Walking down Park Street on a recent Friday night, Larry Simcox was just looking for a place to eat.

He didn’t know the Five Points neighborhood; the visitor from Jacksonville didn’t know Jacksonville at all.

“We told the Uber driver, ‘Take us to a place with bars, a place we can have fun and stay safe,'” Simcox said. “‘Take us to a good place to hang out.'”

Just a few years ago, that wouldn’t have happened.

It’s not just that the area has grown up culinarily, or that a handful of new bars have made the area a more attractive nightspot for Jacksonville residents. Quite simply, there wouldn’t have been many hungry tourists in Five Points a few years ago: Only in the past handful of years has Riverside’s Five Points become the sort of place where cab drivers will drop visitors, where young professionals gather in droves, where there’s a sense that one part of Jacksonville’s future is being created.

That change is good for the few dozen businesses that make up the strip — but not just them.

The increased interest in the neighborhood — one a few blocks long, anchored by a Publix Super Markets Inc. store on one end and Riverside Park on the other — bodes well for more than just the hip hair salons and food-trucks-turned-restaurants that call it home.

That growth also lays out a possible road map for Downtown, providing testimony that Jacksonville can actually support a walkable, urban area.

The Black Sheep effect

Getting to that point took time, though — time and one big project that many credit with shaping the modern Five Points.

It was just over two years ago that Jonathan Insetta’s Black Sheep restaurant opened for business, the culmination of 16 months of construction and years of dreaming. It was a big day for its owners, of course, but also one that had a spill-over effect on the broader area.

Picking Five Points for the first restaurant he would build from the ground up was an easy choice for Insetta, who made his name with Chew and Orsay.

When the chef started learning his trade, he lived in Riverside, attending Florida State College at Jacksonville before heading to the Culinary Institute of America.

“I love the history and heritage of it, the bohemian feel of it,” he said. “When we were looking at spots for Black Sheep, it was the first spot I had in mind. We wanted to be a part of that.”

What has created the “Black Sheep effect” is how the restaurant has achieved two goals: fitting into the funkiness of the area while pulling in a different clientele.

It’s not the only place in the neighborhood that’s done so.

Derby on Park — which features white tablecloths and live music — straddles the same sort of line, as does Hawkers Asian Street Fare a block away.

Black Sheep does it on a bigger scale, though.

“My restaurants have always been able to bring a diverse clientele,” Insetta said.

For Black Sheep, that meant high-end food and handcrafted cocktails, but at a style — and price point — that fit the neighborhood. “I want people to feel comfortable,” he said. “Old-school fine dining can put people off.”

Black Sheep, it should be noted, was where the early evening drinkers congregating at Rain Dogs directed Simcox and his friends.

The value of diversity

Making people feel comfortable is — perhaps has always been — a hallmark of Five Points, the site of the city’s longest-running gay pride event and a place where upscale eateries and dive bars exist cheek to jowl.

If anything, the challenge for Five Points is attracting a new crowd while not scaring off the old.

So far, it’s working, said Tony Allegretti, who among his various other projects is part owner of BREW, the Five Points joint recently named one of the best new coffee shops in the country.

“It’s attracting a broader crowd,” he said about the neighborhood.

Sure, more people with more money are stopping by — “but if you go to Birdie’s [a long-standing bar] and talk about how Five Points is all bankers, you’d get laughed at,” he said. “I think instead of saying it’s becoming high-end, I’d say it’s just becoming more accessible to everyone.”

That was part of the point in setting up Rain Dogs, one of the other half a dozen bars that populate the area.

Christina Wagner, one of the two partners behind Rain Dogs, had been part of the Five Points scene since her days in high school, back in the ’90s. The bars in the area include Wall Street, an older hangout; and Birdie’s, which appeals to a younger crowd.

“I wanted to set up something in between,” she said. “I wanted the type of bar I would want to go to.”

That’s not unusual for the neighborhood.

Five Points merchants, Insetta said, tend to have “very personal businesses that are really heartfelt and expressions of the individuals running them.”

It’s not just the restaurants that fit that mold: The Sun-Ray Cinema, which dates back to the 1920s, was a labor of love of entrepreneur Tim Massett. Hawthorne Hair Salon showcases the vision of founder Jim Stracke.

“It’s a pretty tight community,” Insetta said. “Hopefully we maintain the integrity of the neighborhood. It’s a special place.”

For Five Points, then, the challenge is to showcase that urban vibe and continue to grow while not becoming a victim of that success.

The neighborhood has gone through one boom-and-bust cycle before, when the success of retailers about 15 years ago led landlords to raise rents.

Soon enough, many of the storefronts were empty — setting the stage for the recent renaissance.

The bridge

As much as serving as its own little bright spot in the city’s retail landscape, Five Points also offers the hope of showing a way forward for the urban core.

Five Points displays much of what Downtown partisans dream of: a walkable area with a mixture of streetside retail; a lunch crowd plus nightlife; retailers and restaurants … and residential just a few blocks away.

“If you look at the last 10 people who opened in Five Points, I guarantee they all looked Downtown,” Allegreti said.

The hope now is that the neighborhood’s success might make it ever so slightly more likely that Downtown becomes more attractive to the next hipster entrepreneur.

If, at least, all the dominoes fall into place.

“I’m excited to see where the area goes when Brooklyn is open,” Wagner said. “I think Brooklyn fills the gap between Riverside and Downtown.”

The dominoes

The theory goes like this: Five Points (and the nightlife complex that has sprung up on King Street) show that Jacksonville can support an urban lifestyle … at least in a place like Riverside, which has a strong residential base.

The big question mark lies between Five Points and Downtown proper: the Brooklyn redevelopment.

The stores that are opening there now are already drawing more people to the Riverside-Brooklyn corridor — and once the residential buildings open up, there will be people living nearby, looking for things to do, places to go, people to meet.

The next logical frontier: Downtown.

“I honestly think it’s going to connect the area,” said Matthew Clark, vice president of retail at Prime Realty Inc.

As Five Points heated up in the past few years — the rebirth of the Sun-Ray Cinema in 2011, the 2012 opening of Black Sheep, the 2014 opening of Hawkers — more national and regional retailers have started eyeing the area, Clark said.

“Retail in Five Points has just blown up,” he said. “There’s a lack of retail space there now — and that’s a good thing.”

In part, a good thing for the developers behind Brooklyn: In Five Points, rents have gone from around $14 a square foot to around $18 to $20 a square foot. In the newly built Brooklyn Center, small shop space is around $20 a square foot.

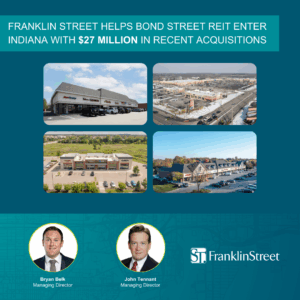

What needs to happen next, said Carrie Smith, regional managing partner of Franklin Street commercial real estate, is people moving into Brooklyn — and then people clamoring to move Downtown.

“Because Riverside and that corridor has been on retailers’ minds as a place where tenants can do good volume, selling tenants on Brooklyn, specifically on Brooklyn Station, has been an easier pitch,” she said.

That means there’s not much space left in Riverside: CoStar Group data showed a 3.1 percent vacancy rate at the end of 2014.

What remains to be seen is how many people actually move into Brooklyn — and how many other people want to live in the urban core.

“We need to see people genuinely want to live in an area that’s more walkable,” Smith said. “If there’s more residents, that will spawn more retail.”

If 220 Riverside gains traction, she said, “that’s a good sign we can start pushing Downtown.”