Publix Super Markets’ competitors are outflanked in South Florida. The beloved brand dominates by sheer force of real estate, and the region’s landlords are happy to let Publix conquer more of it.

The Lakeland-based company has been taking over the tri-county area for decades, and it’s keeping competitors out by opening multiple stores in close proximity.

“The way Publix competes is to open stores and not let any other brands in, so they might open a store within 2 miles of another,” said Cammi Goldberg, director of leasing and landlord representation at Franklin Street.

“It’s easy for the company to rack up locations fast because Publix knows what shopping center landlords want: solid-credit anchors that are flexible about their store model and are selling goods that locals can’t live without.

Winn-Dixie lost out to this strategy long ago.

Stephen Bittel, chairman of Miami Beach-based Terranova Corp., said the two brands had great balance sheets and strong customer loyalty but Publix gained headway after Winn Dixie succumbed to rocky leadership decisions in the mid-1990s. Now, the Southeastern Grocers subsidiary is closing stores across the country and can no longer even compare itself to Publix, the clear victor in South Florida.

To be sure, Winn-Dixie and other brands aren’t giving up the battle for South Florida’s 6 million potential customers.

Trader Joe’s opened its first area store in 2013 and quickly expanded to six locations, much to the excitement of its large fan following. The speciality grocer has two more stores coming soon – in Davie and Fort Lauderdale

Whole Foods Market opened four new stores in the tri-county area this year, bringing it to 15 locations.

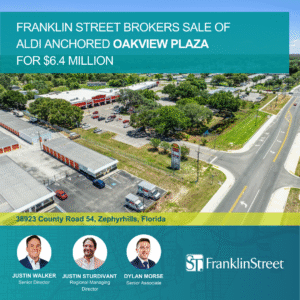

Aldi has 20 stores in the area, with more in the works. It’s also opening up a South Florida distribution center soon.

Although many of these brands don’t consider themselves direct competitors with Publix, a full shopping cart checking out at one grocery store means fewer dollars spent at another.

Publix, on the other hand, doesn’t seem too concerned about the new players or their plans for expansion.

David J. Livingston, grocery analyst and president of Milwaukee-based DJL Research, said Publix could “care less” about Aldi. Sure, it sells groceries for less, but it has minimal impact on Publix’s business.

The Fresh Market, Target, Winn-Dixie, Hispanic grocers and wholesalers like Costco also have a presence in the region and are different fits for different consumers. Wal-Mart (NYSE:WMT), however, is Publix’s largest mainstream competitor, with about 65 locations – six of which opened this year.

Publix has 230 locations in South Florida, with two more coming to West Palm Beach and others opening soon in Doral and Weston.

Publix doesn’t tip its hand regarding the amount of time and money it invests in securing locations, but some sites can take years to nail down.

“Evaluating a site depends on many variables and expected growth of the area,” spokeswoman Nicole Krauss said in an email exchange. “Sores in our Miami division (which includes Monroe County) are in close proximity because the population density of the area can sustain business.”

Flexibility and persistence is the reason Wal-Mart, the world’s largest retailer, has trouble expanding as rapidly here as Publix, JLL VP Justin Greider said.

Wal-Mart’s “business model is to repeat what they’ve done everywhere, and their model doesn’t meet that South Florida demand,” he said. “It’s difficult for them to grow here because they’re locked into a very specific grocery box.”

Publix is willing to contract its stores to about 26,000 square feet and expand them to 60,000 square feet to fit into a space. It puts parking wherever it can – whether it’s on the roof, or below the store.

In Miami’s Brickell neighborhood, where square footage is expensive and scarce, Publix opened smaller stores.

Publix is even more creative with its projects in Sunny Isles Beach and Coral Gables, where it proposed plans to build apartments on top of its stores.

“These deals are more expensive, but in the long run, it’s all about market share,” said Paco Diaz, senior VP with CBRE. Publix has been doing this sort of thing for 30 years, the commercial real estate veteran added.

Ensuring more control in the market, Publix has been buying shopping centers where it is the anchor.

Most recently, the grocer secured a Hollywood shopping center for $39 million, or $432 a square foot, in June. It bought another shopping center in Fort Lauderdale for $22.5 million, or $450 a square foot, in April. Both centers were sold by Stiles, a longtime partner of Publix.

Stiles declined to speak further about the partnership. In its most recent deal, announced July 16, Publix purchased a West Palm Beach retail plaza for $16.25 million from Equity One.

“That’s what you can do when you have the best balance sheet in the business,” Terranova’s Bittel said.

With few ways to wrangle for more real estate and not enough time to build up the reputation Publix has in the market, grocers are finding other means to snare more market share, like expanded prepared food sections and delivery services.

Instacart, a grocery delivery service that recently expanded to Miami-Dade County, says its employing hundreds of personal shoppers like Jessie Perez.

Shortly after the Business Journal met up with the Miami-Dade College student at a Whole Foods on Biscayne Boulevard, his phone began to buzz with an order that was supposed to be delivered to North Miami in 18 minutes.

Promoting its delivery-in-less-than-an-hour service, Instacart says it’s quickly growing in popularity in South Florida, but won’t reveal how many deliveries it has made since launching here.

Instacart GM Nick Freidrich said Miami has hit the company’s delivery volume goals faster than the 15 other cities where it operates, and it’s seeing hundreds of customers sign up each day.

The San Francisco-based company partners with Whole Foods, Winn-Dixie, BJ’s Wholesale Club and Petco, making it easier for anyone who wants to avoid South Flroida’s notorious traffic to shop somewhere other than Publix.

“I think that delivery is definitely going to be a growing factor for the very dense, very urban markets where it’s harder for people to get around,” JLL’s Greider said. But, there’s no substitute for the hands-on grocery shopping experience, and that is not going away, he said. It’s why he believes grocery delivery has had trouble getting of the ground.

Publix experimented with grocery delivery in South Florida from 2001 to 2003. It also tried to meet shoppers half-way in 2012 with Publix Curbside, which has since been discontinued.

Shipt, a Birmingham, Alabama-based company with no ties to the grocer, will begin offering delivery from Publix stores across South Florida on Aug. 18, but it’s too early to tell how long it will last.

Livingston said grocery delivery will continue to have a “minimal” effect on the brick-and-mortar grocery experience – and Publix has a shopping experience to be reckoned with.

Publix was named among the most reputable retailers in the U.S., according to the Reputation Institute, even though it only has stores in six states across the Southeast. It was second only to Amazon.com (Nasdaq: AMZN).

Despite many brands with solid reputations entering the market, – Colorado-based Lucky’s Market, for instance, is among those seeking space – few say any other retailer can potentially dethrone Publix in the South Florida arena.

One way they’re trying is to let go of the big-box store model. Many retailers are shrinking to fit wherever they can to get a piece of the market share.

Trade Joe’s and Aldi fit into smaller parcels and do not typically attract the same shoppers as Publix does. Target opened its first TargetExpress in Minneapolis’ Dinkytown commercial district, testing a 20,000-square-foot store model to see how they fare in urban cores. And there’s a growing regard for smaller stores in South Florida, said Jame Sturgis, sales director at Metro 1 Broward.

“We’re seeing a preference for smaller concepts that are more modern,” he said, noting Wegmans, which he says has a small-store model and was named the company with the best corporate reputation via an annual Nielsen poll. But the Rochester, New York-based grocer has yet to find its way to South Florida.

Publix may already have an answer for those brands that could move on its territory: Sources told Orlando Business reporter Anjali Fluker that the grocer was working on a 20,000-square-foot prototype in May 2014, and The (Lakeland) Ledger says the rumors resurfaced last month when representatives from the chain met with Gainesville planning staff members about the prototype possibly debuting near the University of South Florida.

It would allow Publix to occupy even more real estate and continue to keep the likes of Kroger (which opened 7,500 square-foot-stores under the Turkey Hill brand), Fairway Group Holdings Corp. (which announced a smaller prototype, Hudson Yards) and any other contender who wants a piece of the Publix sub that is South Florida.

Whole Foods also revealed details about its own lower-priced, millennial-focused chain of grocery stores called 365 by Whole Foods, according to Tampa Bay Business Journal reporter Ashley Gurbal Kritzer. Those are expected to have smaller footprints.

If Whole Foods can pull of a middle-market concept, Kritzer reports, it has the potential to be a legitimate competitor to Publix. But with few details about the concept, that’s yet to be seen.

Said Terranova’s Bittel: “As long as Publix controls so much real estate through ownership or long-term leases, when you add on their great customer service mentality, no one’s ever taking them over.”